Sounding

the

Monsoon

Weaving

the

Nakaiy

Indigenous Understanding Woven with Weather Data

For the full project experience please enjoy the accompany audio tracks and toggle on the audio to the left

Sounding the Monsoon’ is a collaborative project in the Maldives that entwines local knowledge of Huvadhu atoll Gadhdhoo’s women’s weaving with scientific representations of monsoonal climate change. These two forms of climate knowledge are linked by the Maldivian Nakaiy calendar, an indigenous monsoonal calendar; which responds to the rhythms of daily, monsoonal life in the islands. The project’s approach is ‘sounding’, a method of critical listening, collection and archiving of environmentally-linked sound and music, and the performance and remediation of these soundscapes in the Maldives.

މޯސަމީ މޫސުން އިއްވާ އަޑު: ނަކަތްބުރުގެ ތެރެއިން ވިޔުން

މިއީ އިންޑިއާ ކަނޑުގައި ހިނގާ މޯސަމީ ވަޔާއިއޮޔާ އެކުގައި ހުވަދު އަތޮޅު ގައްދޫގައި ޒަމާނުއްސުރެ ހިންގަމުން އަންނަ ތުނޑުކުނާ ވިޔުމުގެ މުއްސަދި އާދަކާދަ އާމެދު މައުލޫމާތު އެއްކުރުމަށް ހިންގާ ރިސާޗެއް. މިކަމުގެ ތެރެއިން ދިވެހި ނަކަތްތެރިކަމާއި، ހުވަދޫ އަތޮޅާއި އިންޑިއާ ކަނޑުގެ އައްސޭރިތަކާމެދު އުފެދިފައިވާ ދަތުރުފަތުރާއި، ވިޔަފާރި، އަދި ސަގާފީ އުނގެނުމުގެ ގުޅުންތަކާ ބެހޭ ވާހަކަ، ލަވަ، އިލްމު، މިއުޒިކު، ބަހުރުވަ އަދި އާދަކާދައާ ބެހޭ މައުލޫމާތާއި އަޑުތަކުގެ ރެކޯޑިންގ އެއްކުރީން. ވަކިން ހާއްސަކޮށް، ގައްދޫއަށް ހާއްސަ ތުނޑުކުނާ ވިޔުމުގެ ކަންކަމާބެހޭގޮތުން އެމަސައްކަތް ކުރާ ފަރާތްތަކާ ބައްދަލުކޮށް، މަސައްކަތްކުރާ ގޮތުގެ މައުލޫމާތާއި، މަސައްކަތާ ގުޅުންހުރި މާހައުލުތަކުގެ އަޑުތައް ރެކޯޑު ކުރެވުނު. މި މައުލޫމާތުތައް އެއްކުރުމަށްފަހު މިތަނުގައި ޝާއިއު މިކުރަނީ ގައްދޫއާއި އަދި ވަށައިގެންވާ މާހައުލާބެހޭ މައުލޫމާތު އެއްތަނަކުން ފެންނާނެ ގޮތަށް މެޕުކޮށް، މިކަމާ ޝައުގުވެރިވާ ފަރާތްތަކާ ހިއްސާކުރާ އާއްމު އާކައިވެއްގެ ގޮތުގަ.

މޯސަމީ މޫސުން އިއްވާ އަޑު: ނަކަތްބުރުގެ ތެރެއިން ވިޔުން

މިއީ އިންޑިއާ ކަނޑުގައި ހިނގާ މޯސަމީ ވަޔާއިއޮޔާ އެކުގައި ހުވަދު އަތޮޅު ގައްދޫގައި ޒަމާނުއްސުރެ ހިންގަމުން އަންނަ ތުނޑުކުނާ ވިޔުމުގެ މުއްސަދި އާދަކާދަ އާމެދު މައުލޫމާތު އެއްކުރުމަށް ހިންގާ ރިސާޗެއް. މިކަމުގެ ތެރެއިން ދިވެހި ނަކަތްތެރިކަމާއި، ހުވަދޫ އަތޮޅާއި އިންޑިއާ ކަނޑުގެ އައްސޭރިތަކާމެދު އުފެދިފައިވާ ދަތުރުފަތުރާއި، ވިޔަފާރި، އަދި ސަގާފީ އުނގެނުމުގެ ގުޅުންތަކާ ބެހޭ ވާހަކަ، ލަވަ، އިލްމު، މިއުޒިކު، ބަހުރުވަ އަދި އާދަކާދައާ ބެހޭ މައުލޫމާތާއި އަޑުތަކުގެ ރެކޯޑިންގ އެއްކުރީން. ވަކިން ހާއްސަކޮށް، ގައްދޫއަށް ހާއްސަ ތުނޑުކުނާ ވިޔުމުގެ ކަންކަމާބެހޭގޮތުން އެމަސައްކަތް ކުރާ ފަރާތްތަކާ ބައްދަލުކޮށް، މަސައްކަތްކުރާ ގޮތުގެ މައުލޫމާތާއި، މަސައްކަތާ ގުޅުންހުރި މާހައުލުތަކުގެ އަޑުތައް ރެކޯޑު ކުރެވުނު. މި މައުލޫމާތުތައް އެއްކުރުމަށްފަހު މިތަނުގައި ޝާއިއު މިކުރަނީ ގައްދޫއާއި އަދި ވަށައިގެންވާ މާހައުލާބެހޭ މައުލޫމާތު އެއްތަނަކުން ފެންނާނެ ގޮތަށް މެޕުކޮށް، މިކަމާ ޝައުގުވެރިވާ ފަރާތްތަކާ ހިއްސާކުރާ އާއްމު އާކައިވެއްގެ ގޮތުގަ.

The Nakaiy

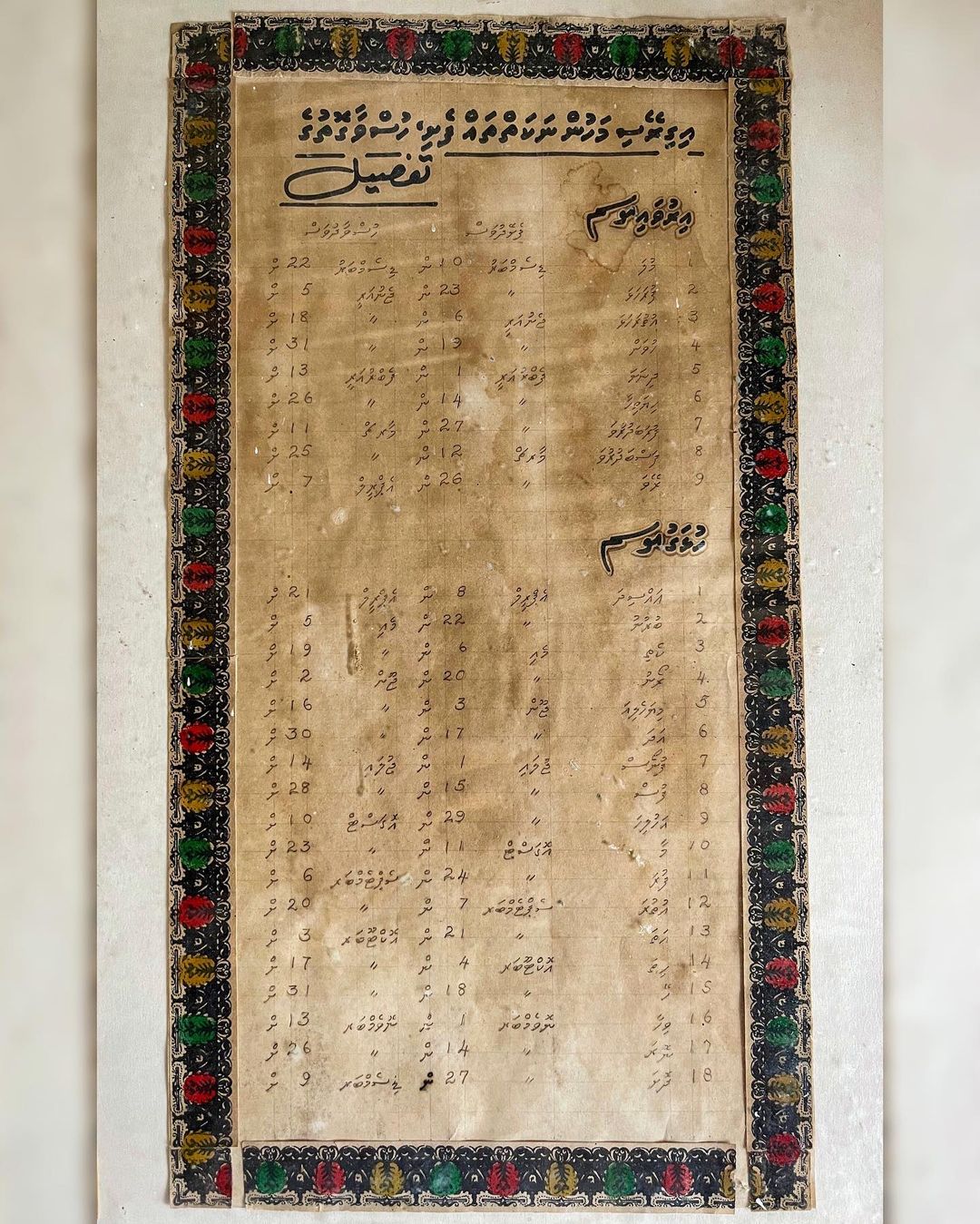

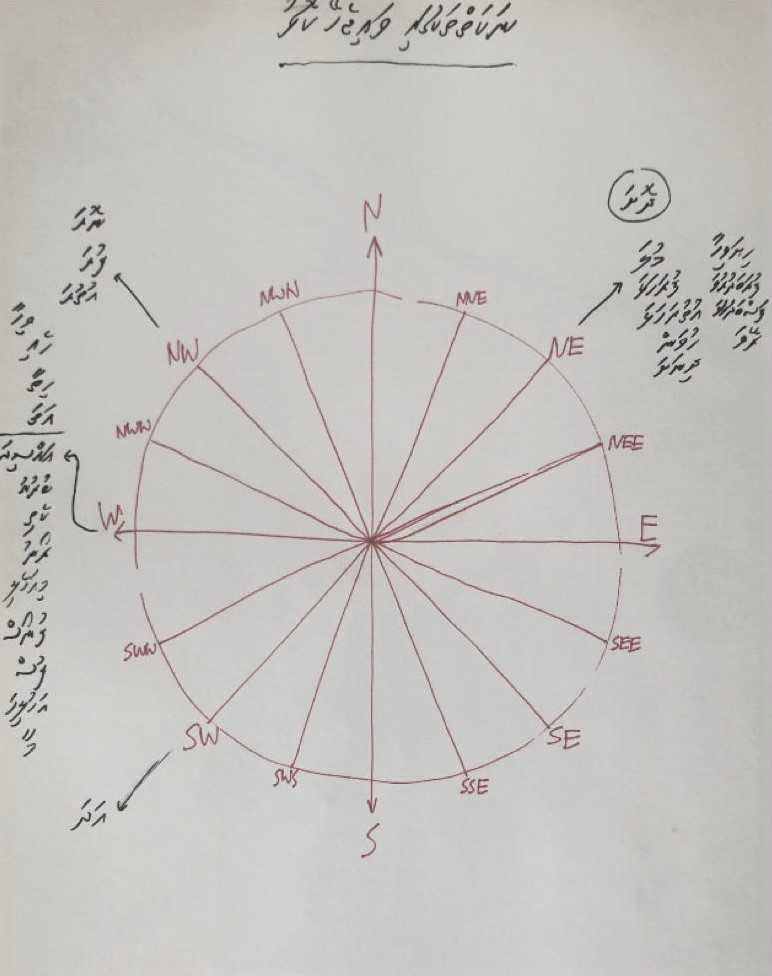

The seasons in the Maldives are dictated by wind direction: the Iruvai monsoon comes from the NE, the direction of the Indian subcontinent, and the Hulahangu monsoon with winds from the SW, pick up moisture as it moves over the Indian Ocean. These two monsoons were customarily divided into 27 or 28 Naikay.

The

Nakaiy is a Maldivian pre-Islamic indigenous calendar based on monsoonal wind

direction. The year's two distinctive seasons are divided into 27 movements

that historically governed life in the Atolls. This weather model is now in an

uncomfortable relationship with the changed climate and rhythms of life.

Through a method of sounding, we have attempted to map complex weather data

from 2002 to 2022 through the ancient Nakaiy model. Collecting oral histories,

folklore, music and magic we have attempted to weave together multiple forms of

knowing the weather.

![]()

The Nakaiy was based on the lunar stations as the moon passes in front of constellations in the ecliptic. This calendar divides the ecliptic into 27 segments named after the prominent constellations of the segment. The constellations are called Nakaiy (Sanskrit nakshatra). Nakaiy refers to the divisions of the stars and each division is named after a particular star. The Dhivehi names of the Nakaiy are closely related to Sanskrit so it is evident that this system came to the Maldives from India (Amin, Willets & Marshall, 1992). Each Nakaiy has 13 or 14 days and is fixed with the solar year. Hulhangu (the rainy or wet season) has 18 Nakaiy and Iruvai (the dry season) has nine Nakaiy. Hulhangu monsoon is approximately from 8th April to 9th December and Iruvai monsoon is from 10th December to 7th April. (Adam 2022: 18-19)

![]()

The Nakaiy system as a weather/auspiciousness calendar has been used in fishing and life in Islamic traditions too, into the 21st century. Its significance only started diminishing recently. The Nakaiy was deployed in a powerful 2019 political campaign. The remnants of the posters and stencils are seen throughout the Maldives.

![]()

The Nakaiy was based on the lunar stations as the moon passes in front of constellations in the ecliptic. This calendar divides the ecliptic into 27 segments named after the prominent constellations of the segment. The constellations are called Nakaiy (Sanskrit nakshatra). Nakaiy refers to the divisions of the stars and each division is named after a particular star. The Dhivehi names of the Nakaiy are closely related to Sanskrit so it is evident that this system came to the Maldives from India (Amin, Willets & Marshall, 1992). Each Nakaiy has 13 or 14 days and is fixed with the solar year. Hulhangu (the rainy or wet season) has 18 Nakaiy and Iruvai (the dry season) has nine Nakaiy. Hulhangu monsoon is approximately from 8th April to 9th December and Iruvai monsoon is from 10th December to 7th April. (Adam 2022: 18-19)

The Nakaiy system as a weather/auspiciousness calendar has been used in fishing and life in Islamic traditions too, into the 21st century. Its significance only started diminishing recently. The Nakaiy was deployed in a powerful 2019 political campaign. The remnants of the posters and stencils are seen throughout the Maldives.

Keyolhu Ahmed (Kondey)

GDh Gadhdho, 11/01/2023

Interviewed At Seenuge

![]()

07:18 - “...About the changes that are occurring in the seasons (moosun), what I can say is that, then, the wind did change to coincide with the Nakaiy. Now, changes to the winds don't come with Nakaiy. So what happens is, Allah makes things happen among a people according to how they collectively wish for things to happen, right? In that sense, we were only able to travel then, when the winds came.

So, that is how Allah makes it happen for us. That is what I will say about it.

Is that so... now we don’t wish for it?

Now we don’t have a need for the winds. Now we don’t have a care for whatever way the wind blows. We can leave on the engine. Isn’t that right? So we needed it then... Now, I remember when the boats don’t come back after travelling to Male’, the people of this island will go with bondibaiy (rice pudding), there is a Ziyaaraiy (shrine) in Gan, when you arrive near the Ziyaaraiy, the path from to Ziyaaraiy to the shore, the whole path would be cleared. It would have been cleaned. Then once they reach it, they recite what they recite, say their prayers, pray for the winds to turn, and then head back...and by the time the sun rises the next morning the winds would have changed.

These are things that have happened, you know? If you were to ask others also you will know these things. For those winds you would go to that shrine. Once there, having recited what they recite, eaten the bondibaiy, read the salawat and returned, the next day, roughly speaking within two days the winds do change. The winds change and the boats do return.”

GDh Gadhdho, 11/01/2023

Interviewed At Seenuge

07:18 - “...About the changes that are occurring in the seasons (moosun), what I can say is that, then, the wind did change to coincide with the Nakaiy. Now, changes to the winds don't come with Nakaiy. So what happens is, Allah makes things happen among a people according to how they collectively wish for things to happen, right? In that sense, we were only able to travel then, when the winds came.

So, that is how Allah makes it happen for us. That is what I will say about it.

Is that so... now we don’t wish for it?

Now we don’t have a need for the winds. Now we don’t have a care for whatever way the wind blows. We can leave on the engine. Isn’t that right? So we needed it then... Now, I remember when the boats don’t come back after travelling to Male’, the people of this island will go with bondibaiy (rice pudding), there is a Ziyaaraiy (shrine) in Gan, when you arrive near the Ziyaaraiy, the path from to Ziyaaraiy to the shore, the whole path would be cleared. It would have been cleaned. Then once they reach it, they recite what they recite, say their prayers, pray for the winds to turn, and then head back...and by the time the sun rises the next morning the winds would have changed.

These are things that have happened, you know? If you were to ask others also you will know these things. For those winds you would go to that shrine. Once there, having recited what they recite, eaten the bondibaiy, read the salawat and returned, the next day, roughly speaking within two days the winds do change. The winds change and the boats do return.”

Weaving

About ten or so Gadhdhuan Thundukunaa weavers now remain. Some of them have moved to the capital Male’ with their families, looking for better employment and education. Younger women are not involved in the work now as it is not possible to earn a living through Thundukunaa weaving. Moreover, the survival of the wetlands of Fiyori, from where the grass for Gadhdhoo mats are sourced, is in a questionable state due to various changes in the environment and local policy implementation methods.

“I tell you, if I start weaving this

mat, I don’t

have to think about anything, your

mind does not hold anything else in it… if you start weaving, weaving, weaving like this, mind is fresh… you don’t have to think about anything else… your mind is always inside the loom…

If I find myself troubled with something, I set up my frame, settle my feet into it and it’s OK, Yes, my mind is really invigorated!”

![]()

![]()

If I find myself troubled with something, I set up my frame, settle my feet into it and it’s OK, Yes, my mind is really invigorated!”

The weaver’s loom was traditionally made with Dhigga (Sea hibiscus). Vaana gas in Gadhdhuan dialect, Vaana is the thread taken from the tree's bark made into threads (Vaka is the name in common Dhivehi dialect). Now cotton thread is more commonly used due to difficulty in acquiring Vaana.

Ahigas (Indian mulberry) - the root of Ahi is used in the creation of a yellow dye, along with turmeric colouring."

Sounding

Weavers dye makers

Healers magicians

Historians storytellers

Navigators seafarers

Determiners of auspiciousness

Growers and qaib researchers

Nurturers of earth

In conversation…

We met Abdul Wahhab on the verandah of Maagasdhoshuge on the night of 7th January 2023, the day we arrived in Gadhdhoo. It was the second day of Uthuruhalha, the third Nakaiy of Iruvai monsoon. Zahir, our host recommended that we meet Wahhab, a retired navigator from Gadhdhoo.

Wahhab told stories of how Gadhdhuans travelled the seas on sailboats in the early times and about the history of trade and travel in the region in relation to seasonal (monsoonal) weather and winds, and of navigating through his life among the ambient political realities that surround.

Nevi, Abdul Wahhab, Gadhdhoo

“Sometimes, depending on what happens, Kethi ends, Roanu also ends, and when Miyaheli comes calmness sets in. If the winds are low too there might be a stopover. When Miyaheli arrives, the wind may change to the southern side a bit. If that change happens too we might have to wait. In that sense, sometimes, very rarely it may happen that way, we may have to wait for up to two months, in Thaa atoll. Thaa atoll, near Veymandoo, in front of Veymandoo there are two reefs.”

Following Sounding the Limits of Life (2015) by anthropologist Stefan Helmreich, we use “sounding”—as investigating, fathoming, listening—to describe the form of inquiry appropriate for tracking meanings and practices of the biological, geological, meteorological, aquatic, and sonic in a time of global change and climate crisis. The notion of ‘fathoming’ has a productive double valence